By Katie Gatens

San FermÃn is a festival dating back to medieval times, and is otherwise known as the Running of the Bulls. It takes place in Pamplona, Spain during the second week of July. It is a controversial festival, and probably the most well known of all of those in Spain, due to the brutal nature of bullfighting and the fact that it is an event centred around the killing of 48 bulls throughout the eight-day festival. Bull fighting has already been made illegal in a few Spanish provinces, which hopefully will extend to include the whole of Spain.

This year, San FermÃn has not gone unnoticed by animal rights protesters; 48 members of PETA shockingly posed naked in coffins in Pamplona, to represent each bull killed, whilst poet Benjamin Zephaniah posted an emotive article on bull fighting on The Guardian website. Studying Spanish at university, I knew about the origins of bullfighting in which the bull is revered. Unlike fox hunting where the foxes are viewed as vermin, the bull is a sacred animal, and bullfighting has origins in the sacrificial offering and the worship of the animal; the bull is, after all, a symbol of Spain.

In my opinion, bullfighting is wrong, but it didn’t stop me from heading to the festival last year to see for myself whether this is an important Spanish tradition, ingrained in the country’s history and culture, or whether it is an unnecessary butchering of animals.

I made the 10-hour coach trip from Barcelona to Pamplona. Approximately one million people visit Pamplona each year for the festival, which is a huge boost for the city’s economy ““ the event is an important economic stimulus in a country that has been one of the worst affected by the crippling economic crisis. Some Spaniards are trading morality for economic security and this spectacle brings in a slew of tourists, all willing to spend money during the festivities.

When I arrived in Pamplona, I was welcomed by an all night — last-night-on-earth — style party, which repeats itself every night of the festival. The whole city pours into the streets, in a flurry of white and red sashes and neckerchiefs, partying as if there’s no tomorrow. There’s musicians, food stalls, open bars and all-night funfair. I’d never experienced a party that takes over an entire city involving nearly everyone living in and visiting it.

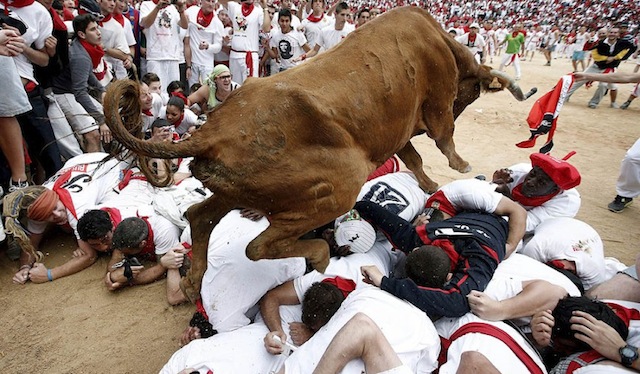

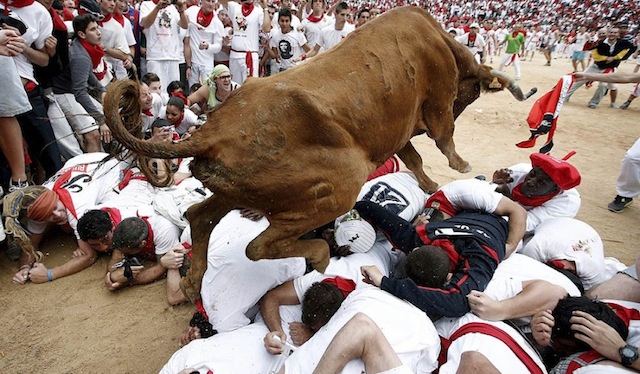

We headed down to the bullring just before 8 a.m., and took our seats to watch the daily half-mile sprint through the city’s narrow cobbled streets. It was at this point that I got a rude wake-up call. Thousands had arrived to be chased by bulls through Pamplona, and thousands more sat in the arena. The atmosphere was violent and as the bulls entered the arena, people began to hit them with sticks, aggravating and taunting them. Spectators were on their feet yelling obscenities and cheering at the sport, and all I could do was sit shocked, wondering how the day had taken such a different turn. Perhaps naively, I hadn’t expected the cheapness of the entertainment on offer. A short video showing the bulls as “˜contestants’ listed their stats, age weight and location. They were hauntingly destined to lose for the sake of cheap thrills.

I sat and wondered what I’d signed up for when I headed to Pamplona. Certainly the carnival atmosphere, firework display and various cultural festivities, but I wondered if this was a necessary prelude to such a brutal and poisonous activity? Would people still come to Pamplona if the bull-run was taken out of the equation or a substitute was provided? I think so, but perhaps not on the scale that they do. Maybe that’s just the sacrifice the Spanish government has to make in order to restore morality to the festival.

I went to Pamplona expecting to find some worthy traces of art, history and culture in this heavily criticized, but perhaps misunderstood sport. I did not. I found instead an outdated, cruel “˜sport’ where, at the end of the day, there are no winners.

About the Writer

Katie has just graduated from the University of Leeds where she studied English and Spanish. She’s been writing for lamono, a multilingual arts and culture magazine for over a year, and lived in Barcelona last summer working for them and has also written for British Airways’ High Life magazine. Katie is interested in the history of countries, and could never visit a place without visiting the cathedrals, ruins or museums there. She’s been inter-railing around Europe for three years and got through a ton of books on the way. Her twitter is @katie_gatens